West Berliners crowd in front of the Berlin Wall on November 11, 1989, as they watch East German border guards demolishing a section of the wall in order to open a new crossing point between East and West Berlin.

There’s something about a wall. The restrictions. The definition of what’s mine and what’s yours. The very sense of ensuring you have to work a little bit harder to experience the other side if you are even allowed to do so. As Robert Frost wrote in his remarkable poem “Mending Wall,” there is something subversive about a wall. A wall is an angry piece of construction. A wall possesses no beauty or aesthetic sense. It divides rather than unifies. Why is it there in the first place? Who is trying to keep who out or who is trying to defeat whom? Almost from the moment of its birth, a wall is an insult to human freedom, a challenge to those whom it excludes. It was somehow calling out to be “unbuilt.”

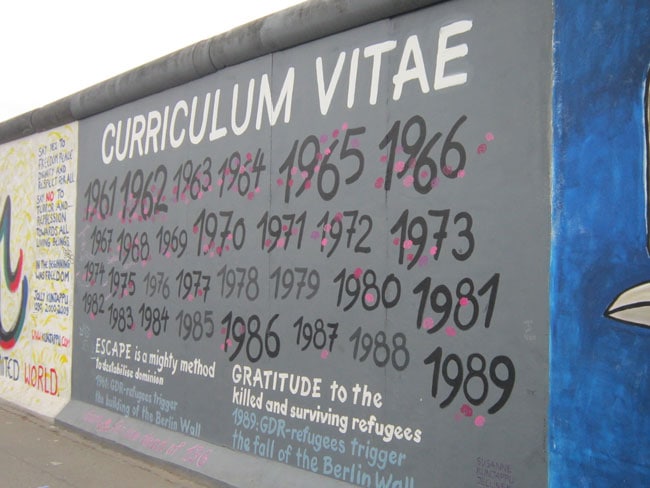

Around November 1990, within a year of the wall coming down, most of the Wall had all but disappeared from Berlin’s landscape. Enormous sections of the Wall were peddled all over the world to governments, companies, and private citizens, while other pieces were reused to make German streets and roads.

Fast forward to 2009, where only approximately two kilometers of the Wall stood tall, almost defiant to the progress of Germany (there were originally 43 kilometers of the Berlin Wall). It was then that protestors literally stood strong in the face of progress to police and bulldozers to protect the last pieces. Willy Brandt, the former mayor of West Berlin and chancellor of West Germany, urged those pillaging the Wall in 1989 to stop because “a piece of this terrible edifice should be left standing as a historical monstrosity” for future generations to see. It too twenty years, but they finally listened.

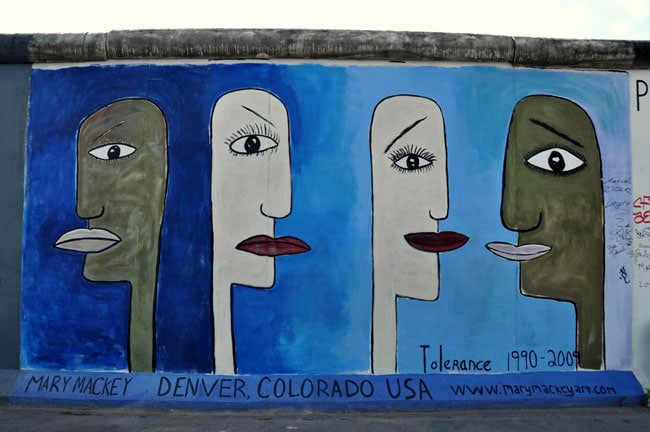

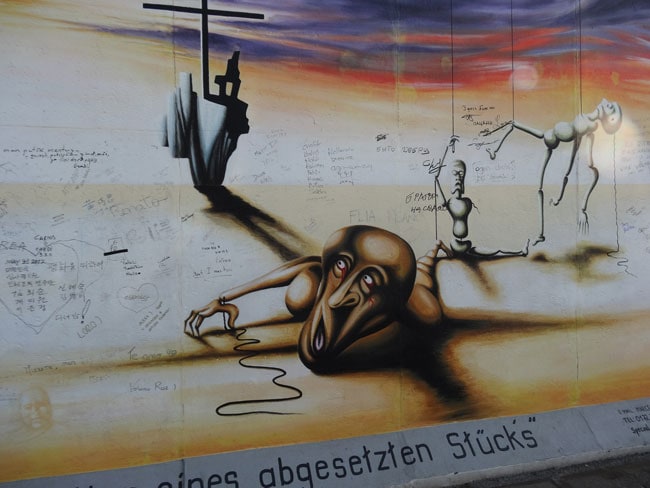

Today, the most popular site to see the Wall is the East Side Gallery. The site where the longest section sits has become famous because of the murals painted after the Wall fell. This section represents the explosion of freedom in 1989, rather than the repression that characterized the Wall until then.

Visiting the East Side Gallery

Images by: Michael Lloyd