“Sure,” I said, waving goodbye. I hadn’t the heart to remind her that the film was shot on a Hollywood sound stage in the 1940s and that Rick’s Café opened in Casablanca only three years ago.

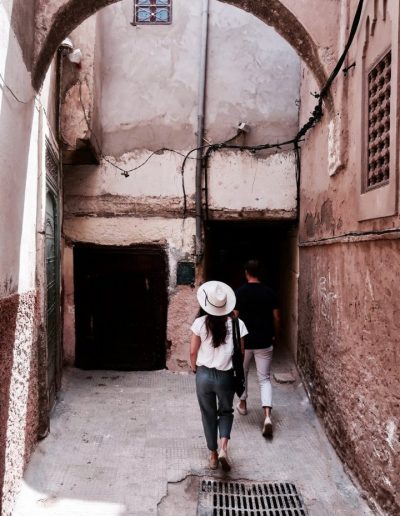

Nine short miles across the Straits of Gibraltar from the Southern Coast of Spain, Morocco, the world’s westernmost Arab country, looks both ways—to its ancient roots in the Middle East and north to its European neighbors. Long an outpost of the Roman Empire, this territory was overrun in the seventh-century by Arab invaders from the Middle East. The conquerors promptly established Muslim rule over the indigenous Berber people and set about building the first of the medieval walled cites, medinas, that have made Morocco a living museum—living because the fabled medinas in the ancient cities of Marrakesh, Fez and Meknes have never stopped teeming with life. Thousands of families live in these timeworn enclaves, meet and greet in their convoluted streets, worship in the mosques of their fathers and shop for the daily bread in their bustling souks.

Then there’s the European Morocco, a legacy of the French who occupied the country from 1912 to 1959. Rather than tamper with historical treasures, they added their own new neighborhoods of broad tree-lined boulevards, modern dwellings, hotels and business centers. By the time they were forced out of Morocco, French had become the second language of the country (English is spoken, too), and bakers were turning out the crustiest breads and flakiest croissants outside of Paris.

When I asked why a group of 20-somethings in designer jeans were gossiping away in perfect French instead of Arabic at the next table in the Marrakesh McDonalds, I was told it made them seem more avant-garde. They are part of a new generation that is leaving the djellaba to grandma in exchange for the freedom of a new international lifestyle. Jetsetters and celebrities like our own Brad Pitt and Angelina are frequent vacationers here. In their wake, the city is seeing the opening of new high fashion boutiques, trendy restaurants with international gourmet menus, and to the tourist’s delight, nightclub restaurants with belly dancing (not a part of the culture here).

Why were we wolfing down Mac fries at 5 p.m. in this city of wonderful couscous and tajines? Because we’d swapped lunch for the dizzying tiled courtyards of one of the city’s best-preserved treasures, the 14th-century Koranic school, Ali Ben Youssef. Then, we clambered around the ruins of the 16th-century Badi Palace, snapping photos of the migrating storks who build their nests on its crumbling towers. (Restaurants in Morocco don’t serve dinner till eight.)

“More than half of the country’s citizens are Berbers, and many of these have blended into mainstream society, but Berber villagers still thrive in the mountains, clinging to their tribal languages and music, tending the sheep and turning out tightly woven carpets that are prized throughout the world.”

Even as I lolled on satin riad pillows with sweet mint tea and honey cakes at my side, Jama el Fna was calling. Within minutes I was hanging onto the seat of my battered red taxi as we dodged a Mercedes, evaded two bikers and skirted a tourist horse and carriage. Finally we met our match, slowing to a crawl behind a spindly-legged donkey lifting his nuzzle to wail at the sky. The family of seven in the cart he was pulling waved at the driver and smiled.

The next morning, hungry for more, I joined the shoppers in the narrow alleys of the jam-packed souk lined with stalls selling everything from raw sheep’s heads to rubies. Hey, make way for that donkey delivery truck with the bathtub on its back.

Nothing could have torn us away from Marrakesh except the lure of the ancient city of Fez, sprawled in a wide riverbed a leisurely day’s ride north. Its own picturesque medina, with 20,000 people, no motorized vehicles allowed, is considered the oldest and best preserved in the world. And it’s a short drive west to the 11th-century city of Meknes and the ruins of Volubilis, the fourth-century Roman city that flourished here.

Fez is a city of craftsmen, with separate streets and districts delegated to each endeavor and product such as musical instruments, wool, jewelry, pottery, kitchenware, wool carding, carpet weaving, shoemaking, tent making, metalwork and a long list of others, tourists welcome. Two of the most extraordinary visits are first, the tannery, where you can watch the workers dipping the skins in giant stone vats of chemicals and colors in a scene from the Middle Ages. And second, the Nejjarine Museum of Wood, housed in a graceful building that is itself a masterpiece of the carver’s art.

Our grand finale was a step back in time at the ruins of Volubilis. Its triumphal arch still looks out over the fields that once fed this city of 20,000, and the miraculously well-preserved mosaic floors of its long gone villas still tell the myths of the gods.

The next morning, on our way to the airport in Casablanca, we stopped to see the country’s 20th-century pride, the King Hassan II mosque. It was opened in l993 on the shores of the Atlantic with room for 25,000 worshippers inside and 100,000 more on its seaside esplanade. The mosque’s 650-foot minaret is lighted at night, and lasers point the way to Mecca.

No, we didn’t make it to Rick’s Café, but we hear there’s another Rick’s in Chicago.